This record took a lot of time to get out. Everyone recorded their verses in their own homes, and sent them in from all over the planet. I produced the full side a, Noblonski side b. I’m not interested in making songs as much anymore. I like to make blocks of music. Creating a twelve inch record like this was perfect, because it allowed me to do just that: make a complete piece of music that others had to rap on. No real choruses. No real overarching theme. Just music.

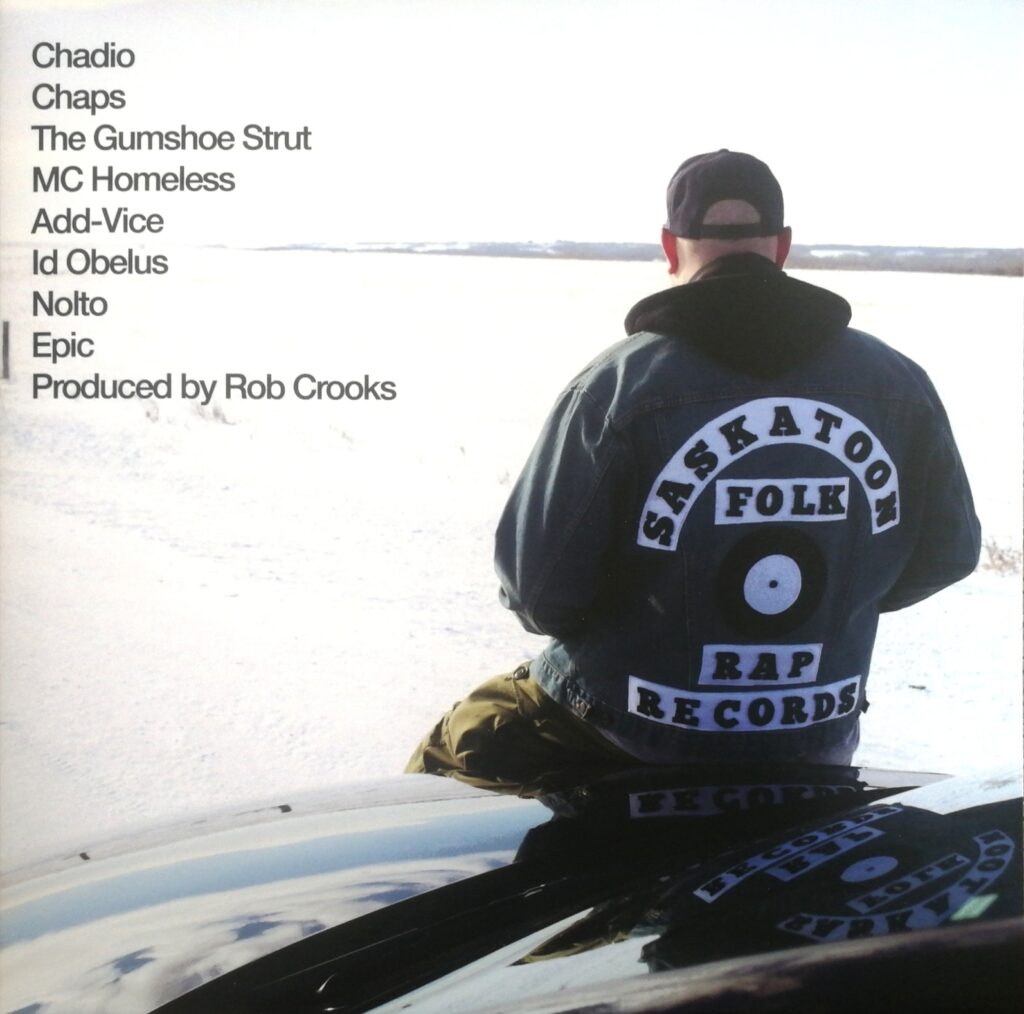

Most of these artists, I’ve never worked with before. All of these connections came out of the formation of Saskatoon Folk Rap Records in 2019. The philosophy around this collective of artists is hard to pin down, as we all have different ideas. There is some coherence in so far as coherence can be nebulous. A couple things that I think this collective represents are as follows.

First I think there is a return to the rich experimentalism of hip-hop in the late 90s and early 2000s. I think in many ways that era was a going back to the late 80s and early 90s when everything was new and fresh. The sound of the golden era was being recreated with every new release. When rap started to get more airplay near the end of the millennium, it started to become a bit formulaic. There was a split at that time between underground and mainstream (or whatever terminology you want to use). The underground was going back to the golden era but in new ways, using the tools of the trade to create new pathways for the music. Jay-Z in many ways was just as inventive as any underground rapper, mind you. But rap’s popularity was becoming such that it was drowning out other expressions so that even people where I’m from were trying to recreate New York or LA rap. We want to make rap that sounds like it comes from where it comes from.

Secondly, we want to release physical music. Records, tapes, CDs. I can’t say this is a rejection of streaming or a romanticism of a bygone past. Streaming marks a vast improvement from when I had so much music on my laptop I couldn’t download a PDF. But its also undeniable that streaming has changed our relationship to music. So much music is disposable. And it effects the way people make music. If you have to stay relevant, you have to keep producing, which means you have to put less quality into the music to increase the quantity. I personally don’t work like that. Nor am I the type of artist who creates 50 songs to narrow it down to 20 for the album. I craft the music I make, changing it over time, until I am satisfied with it. Putting out physical music is respecting this process.

Thirdly, I’m not chasing an audience anymore. There were times when I felt rejected by the hip-hop community for the music I was making. My beats were starting to become influenced by other genres, such as jungle, garage and post-punk. The BPMs started to rise. I began to experiment with singing. Some purists saw this as a disgrace to hip-hop, and it felt like the hip-hop community in my own city turned their back on what I was doing. I started to seek out other scenes to perform within, but being a sample-based musician, I could never really gain any traction in the synth or dance scene either. What I was missing the whole time, however, was that I did have supporters and fans. Although the majority didn’t get it, some people did. So I’m no longer chasing anything. I’m making what I want to make but putting enough time and effort into it that those who appreciate it will recognize it as such.

Finally, unapologetic sampling. Many artists who make a living off their music don’t have the luxury that I have with regards to sampling. If an artist who depends on airplay has their song banned for a sample, or if they can’t afford to clear the samples they use, they are really screwed. Me, I don’t care. I don’t depend on music for money. If I were to get a cease and desist letter, or something like it, for a sample I used. I would simply release the song on a white label. I don’t believe in intellectual property. I will always sample.